Over a

thousand years ago (788 AD), Shivaguru and Ayamba lived in the village of

Kaladi, in Kerala, India. They

were a pious and benevolent couple who earnestly desired to have children.

On a visit

to the Shiva temple of Trichur, they spent the day worshiping Shiva devoutly

before retiring early. That

night, both of them had the same dream in which Shiva, disguised as a sage,

said to them, “I am pleased with your devotion. You can choose to have either one extraordinary son with a short life

or many ordinary sons.” The

couple replied, “Lord, give us one extraordinary son.”

On a visit

to the Shiva temple of Trichur, they spent the day worshiping Shiva devoutly

before retiring early. That

night, both of them had the same dream in which Shiva, disguised as a sage,

said to them, “I am pleased with your devotion. You can choose to have either one extraordinary son with a short life

or many ordinary sons.” The

couple replied, “Lord, give us one extraordinary son.”

Months

later, Ayamba gave birth to a son who was predicted to become an extraordinary

person. The child was named Shankara, another name for Shiva.

Shankara was only five years old when he had his sacred thread ceremony.

After that, following the custom of the times, he went to live and

study with his guru, a learned teacher.

Shankara

learned of his father’s death on a visit home. He saw his mother weeping and shared her grief. Ayamba grew feebler

after Shivaguru’s death and Shankara spent more time caring for her.

On one

occasion, Ayamba expressed her concern, “Will I ever be able to go to the

river to take a bath?” Shankara

consoled her by stating that she need not go a long distance to the river

because the river would come to her. Then,

he and his friends, with great effort, changed the course of the river to flow

by their house. After this great

show of devotion, his mother was delighted and blessed her son.

As a

teenager, Shankara was distressed by the fragmentation of the country. He felt that he should become a sanyasi, or monk,

and travel across India preaching spiritual unity. As a first step toward this goal, he visited King

Rajashekhara of Kerala and talked with the royal poets. The king was deeply

impressed and invited Shankara to stay and join the group.

Shankara declined, setting his clear goal of

becoming a traveling monk.

Determined

to fulfill this goal, Shankara asked his mother’s permission to become a sanyasi.

She refused, saying, “I am all by myself and old.

Who will look after me? You

should marry and settle here.”

Shankara

was deeply troubled. He was

committed to what he knew was his life’s goal but he would not leave home

without his mother’s permission. He

wondered what he should do. He

did not have long to wait.

One

evening, as Shankara was bathing in the river, a crocodile caught his leg. It appeared he would be dragged to his death.

His mother was on the bank and was greatly alarmed.

Shankara shouted, “Mother, I want to die as a sanyasi, please

give me your permission now!” His

mother could not refuse her son’s final request, so she agreed.

At that

moment, the crocodile released Shankara and disappeared into the river.

Shankara came out safely from the river.

His relieved mother blessed him and said, “Son, you have great tasks

ahead of you. I will not stand in

your way.”

Shankara

accepted his mother’s blessing and left home at the age of twelve. He promised to return at any time she needed him.

As

Shankara traveled northward, he came to Narmada and met the famous sage

Bhagvadpada and his disciples. The

sage greeted Shankara cordially and asked him about his beliefs and

conclusions. Bhagvadpada was

greatly impressed with Shankara’s bold and direct answers.

The sage could discern a clear mind and a depth of knowledge.

He agreed to ordain Shankara as a Paramahamsa Sanyasi, the highest

order.

Sometime

after that, Shankara was meditating when alarmed villagers cried for his help.

The river Narmada was flooding and water was near the hermitage.

Shankara placed his meditation staff at the edge of the rising water

and the water began to recede. The

amazed villagers paid reverence to the power of this holy person.

After

three years with his guru, Shankara had a vision in which the legendary sage

Vedavyasa told him, “I want you to move onwards on your great mission of

uniting India.” Shankara

obtained his teacher’s permission to leave and proceeded on his life-work.

When he

reached Kashi (Varanasi), Shankara was well received by scholars and poets.

Many were attracted to his teaching of Advaita, the oneness of

each individual with the creator. His fame increased as he visited temples and talked with many

scholars. Shankara began

attracting disciples and he established a monastic order.

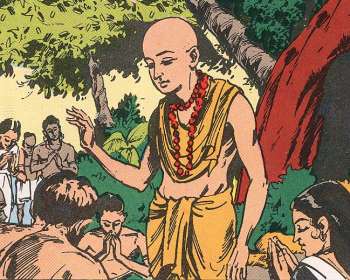

While in

Kashi, Shankara and his disciples were returning to the monastery from their

daily bath in the Ganges when an outcast approached from the opposite

direction. The disciples called

out for the outcast to move aside so they might pass without touching him. The outcast calmly replied, “What shall I move - my body

which is made of earthly elements or my soul which is all-pervading

consciousness?” At that moment,

Shankara had a vision in which it was revealed to him that the outcast was

Shiva in disguise. He suddenly

realized the one reality in all. He

stopped his disciples and said, “He is indeed my guru, regardless of his low

birth.”

This

intuitive flash of insight strengthened Shankara’s convictions and he boldly

taught his Advaitic message to the sages and Brahmins who had believed in

rituals only. He said, “True

happiness does not lie in the practice of mere rituals.

Try to understand the presence of the one reality in all.” This teaching gave a new and larger meaning to

the

narrow definition of religion and was eagerly received by many who heard it.

When at

last Shankara left Kashi, he traveled north to Hardwar and Rishikesh. At the temple in Rishikesh, he found the sacred idol missing. The priests had hidden

the idol in the Ganges river to protect from the raids of the hill-tribes, but

later could not find it. With divine

insight, Shankara went to the river and instructed the priests to look again.

To their utter surprise, the image was found and was ceremonially

installed.

Shankara

next visited the hill-tribes and taught them his powerful message. Many of them reformed their ways and some followed him as he

proceeded on his journey. At

Badrinath, Shankar once again found the idol missing. The

priest pled Shankara to find the idol, which he did, and ceremonially installed

it.

Shankara

and his followers proceeded westward through the Himalayas to Kedarnath and

Amarnath. From there he went

north to Gangotri, the source of the river Ganges.

At this time, Shankara was only sixteen.

His knowledge of the Vedas was extensive and many sages came to him for

clarification and were drawn to his powerful teaching.

Shankara

returned to Badrinath where he stayed for some time writing and giving

discourses. His disciples were

truly dedicated to him, serving his needs and carrying out his wishes.

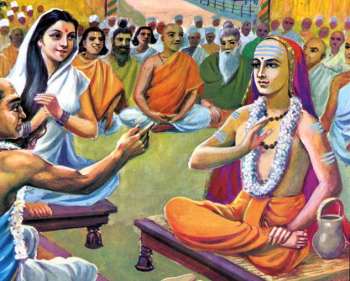

Many of

the Brahmins rejected Shankara’s teachings because of his indifference to

their high social standing and their spiritless, ritualistic approach to

religion. One of the highly

respected Brahmins was Mandana Mishra, whom Shankara challenged to a debate on

eternal truth. Mishra accepted

the challenge and they agreed to take Mishra’s wife, Saraswati, as the judge since

she was known to be learned and impartial.

Saraswati

observed, “How can a sanyasi, who has no experience as a citizen, and

a householder, claim complete knowledge?”

Shankara

replied, “I accept your verdict, Mother.

I need to be wise in the ways of the world.

Give me time.” Saraswati

granted Shankara one year time to gain experience and return to continue the

debate.

Shankara

secluded himself in a cave with only his faithful disciple Padmapada.

When

Shankara explained to Padmapada that he must obtain the experience of a householder,

Padmapada objected, “In what way will the experience of a householder help

in obtaining spiritual perfection? In

fact, it will be an obstacle.”

“No,

Padmapada,” replied Shankara, “spiritual perfection must be obtained in

the battlefield of life itself.”

Then

Shankara revealed his plan. Padmapada,

listened carefully. “I shall

soon enter into samadhi through my yogic powers.

My soul will take flight to another body to gain the experiences of a

householder. Until I come back

and reenter my soulless body, guard me carefully.”

Saying

this, Shankara went into a state of samadhi and his soul traveled to a

town in Vanga Desha, today’s Bengal. There

the king was on his deathbed. When

the king’s soul left its mortal body, Shankara’s soul entered into it. The king’s body revived and no one could tell the

difference. Shankara began to

experience the life of a householder, the joy and the sorrow. Shankara

experienced the responsibilities of a king; the kingdom had to be defended and

law-breakers had to be punished. He

made decisions both great and small that affected other people’s lives.

He was also able to experience the luxuries of a king without becoming

involved and attached.

When

Shankara obtained the needed experience of a worldly life, its good and evil,

he made plans to return to his own body.

Upon his departure, the king’s body weakened and was declared dead. At the same time, Shankara’s body came to life.

Padmapada bowed in reverence as he witnessed the soulless body return

to its former state.

Shankara

returned to Mandana Mishra and plans were made to resume the debate. Both of them were given garlands and the agreement was that

the competitor whose garland withered first would be the loser.

The debate went on for a few days until they reached the topic of

Eternal Truth.

Mishra said, “I

hold that worship and rituals make for happiness here and hereafter.”

Shankara

calmly replied, “Rituals do not bring the highest happiness.

Complete knowledge through the Vedas is the only answer for such

knowledge reveals the one Reality.”

As this

was spoken, the flowers in Misra’s garland wilted and faded.

Mandana Misra understood the message.

He accepted Shankara as his guru.

Mishra was ordained and named Sureshwaracharya.

Shankara,

accompanied by his followers, including Sureshwaracharya and Saraswati,

journeyed south stopping at all the holy places.

At Gokama, a rich man brought his deaf and dumb son for Shankara’s

blessing. Everyone was astonished

as the boy’s speech was restored. The

boy was ordained into Shankara’s monastic order.

At Sringeri,

Shankara founded the Shradha Peetha and put Sureshwaracharya in charge.

They stayed at Sringeri for several months until Shankara had a

premonition and said, “My mother needs me.

I must hasten to her side.”

Shankara

returned to his home in Kaladi and found his mother in poor health. He comforted her and imparted to her the divine knowledge he

had learned in his short life. Ayamba

died peacefully with an enlightened soul. Shankara

carried the body to a corner of the garden and, placing it on a pyre of plantain

stems, cremated it. Orthodox Brahmins in the community objected to a sanyasi

performing what they considered the rites of a householder, even though Shankara

was her only heir. However, they later repented and praised Shankara for his

filial love.

After his

mother’s death, Shankara traveled twice throughout India.

He enjoyed the patronage and protection of kings and scholars.

Many, including members of royal families, gave up their wealth and

position to become his disciples. He

produced a wealth of learned and devotional literature.

Shankara was above the discriminations of sex, wealth, and caste.

Shankara

died at the young age of thirty-two, ending his extraordinary earthly mission.

He witnessed during his lifetime the awakening of spiritual India and the

strengthening of Vedic truth. The

gospel of Shankara – the brotherhood of all humanity, the oneness of truth –

lives on, ever active and luminous. The

lives of Vivekananda, Chinmayanada, and many thousands of others were inspired

by the dedicated teaching of Adi Shankara.

If India can ever be united, it will be by the common bond of Vedic

knowledge.

A few of

Shankara’s sayings:

Just as a piece of rope is imagined to be a

snake in the darkness so is Atman (soul) determined to be the body by an

ignorant person.

Neither by yoga, nor philosophy, nor by work,

nor by learning but by the realization of one’s identity with Brahman is

liberation possible, and by no other means.

A father has his sons and others to free him

from his debts; but he has none but himself to remove his bondage.

![]()